Last month, we looked at the remarkable Samurai armour that went on display for the Other Worlds: Art of Atomhawk exhibition. Today, I’m going to be investigating another object from this exhibition as well as two others from the World Cultures gallery. They’re three very different, beautiful pieces of material culture from three distinct groups of people in Asia, but they all have one thing in common: each object was made by a group of people who practised headhunting.

Headhunting is the custom of taking and preserving a human head after killing the person. While this may seem a gruesome action to many of us today, headhunting has been practised by many different peoples throughout history. It has been the subject of various studies, where scholars have tried to interpret its role within societies. What has often been found is that headhunting had ritual and ceremony as its core functions, themes of which we’re about to explore.

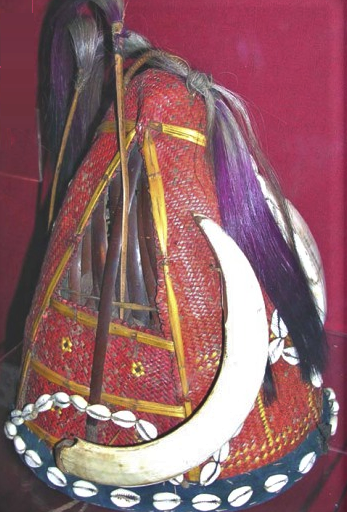

Firstly, let’s go back to the Atomhawk exhibition to see one of the objects on display- a ceremonial hat from the Naga people.

NEWHM : D193 – Naga hat, Atomhawk exhibition

These hats are extremely eye catching, often embellished with boar tusks, feathers and goat hair to evoke the power and courage of the animals in their environment.

Location of the Naga peoples, north-eastern India/north-western Myanmar

The Naga are a group of peoples who live in north-eastern India and north-western Myanmar, and they were well known for headhunting. They didn’t take heads merely to wage war though- the Naga believed that human skulls possessed a life force that could ensure the prosperity of a tribal clan and their crops and animals. According to Naga belief, the human soul is divided into two- the mio (spiritual aspect) and the yaha (the animated aspect). When a Naga person dies, it was thought that the yaha goes on to the land of the dead but the mio remains in the village. It was this mio that led to the property and fertility of a village. The Naga people believed that the mio resided in the head, and so by taking a head the “spirit reservoir” of their village would be topped up. A successful headhunt by a Naga man wouldn’t just bring success to his village. The man himself would also acquire significant prestige and even make him a suitable husband.

During the 20th century, most of the Naga people converted to Christianity and the ritual of headhunting became obsolete. Along with Christian celebrations, many different tribal festivals are still celebrated. It’s during these gatherings that the traditional dress of the Naga people is often worn including the vibrant red headgear.

The Naga people today wearing the ceremonial warrior’s hat

The Naga people had a definite spiritual dimension to their headhunting, but there was also a certain element of prestige attached to the act of taking a head, and for a young Naga man it may well have been an important rite of passage. It appears to be a similar story for the people of Nias Island.

Nias Island, off the coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia

On display in the World Cultures gallery is a large wooden shield that was made by the Nias people. Known as a baluse, it has a large imposing size and a shape that was said to allude to a head of a crocodile – an animal that would instil both fear and awe.

NEWHM : D479 – Baluse shield, GNM: Hancock

The baluse would have been used both for ritual performances and for battle. Centuries ago, the people of Nias lived in a state of conflict, either defending themselves against slave raiders or engaging in inter-tribal warfare. Young men were brought up to become fierce warriors. Alongside warfare, headhunting was also prevalent in Nias society. The act of taking a head was very important and symbolic for the islanders. A young warrior would need to bring a head back to the village before being allowed to marry or sit in on the village council. The more heads a warrior took in battle, the higher his status in Nias society became. And like the Naga, the people of Nias believed that captured heads would bring protective forces to the village.

This theme of community safeguarding can be seen in the headhunting activities of a third group of people, the Ibans of Borneo.

Location of the Iban people, Sarawak, Borneo

At first glance, the beautiful kenyalang on display in the World Cultures gallery would not suggest any links with headhunting. Kenyalang are carvings of rhinoceros hornbills, a large bird that could be found in the rainforests of Borneo.

NEWHM : D723 – kenyalang figure

A Rhinoceras Hornbill

They were created and carved by the Iban people, who like the Naga and Nias peoples, used to practise headhunting. The kenyalang would be used in special ceremonies that called upon supernatural entities for help to ensure success during a future raid. Hornbill carvings like the one on display in the GNM would be mounted on top of a tree trunk and pointed towards an enemy. The spirit of the hornbill would be encouraged by the Iban to fly over and enter the spiritual domain of the targeted community and destroy its will. It was literally a threatening notice to a specific enemy. The effigy of a rhinoceros hornbill was used as this bird was a powerful flyer within the rainforest. The act of taking a head for the Iban came with a heavy responsibility. They believed that the soul of the head would watch over the household that it graced. The Iban also believed that the spiritual power that came from the head was directly related to the character of the man it was taken from , and so only the heads of enemy warriors were taken in battle.

So there we have it. Three different objects, but some of the stories that lie within them are all about headhunting. The collection of human heads for these peoples were not merely seen as trophies or spoils of war. It is evident that the practise was incorporated into a system of complex beliefs associated with spiritual power and protection and was often an important rite of passage for young men. The rise of Christianity in Asia and the conversion of many of the Naga, Nias and Iban peoples meant that headhunting declined and finally ended in the 20th century. However, as we can see, their stories can still be found within some of the objects on display in the GNM.