My name is Emily Needle. I am a 3rd year History student at Newcastle University on a work placement at the Great North Museum Hancock: Library. I am fortunate to be able to look at and read some wonderful old and rare books every time I come in for my placement. This week I came across some fascinating material that discusses the Great Flood on the Rivers Tyne, Tees, Wear and Eden, on the 16th and 17th November 1771, which is of course 244 years ago to date, and seems relevant with the amount of rain we’ve been having this past week in 2015!

It is hard to imagine such a disastrous natural calamity happening today where I live and study, but of course it can happen anywhere at any time, and unfortunate inhabitants of Newcastle in the eighteenth-century experienced first-hand what was described by contemporaries as ‘the most dreadful inundation that ever befell that part of the country.’ Incessant rainfall from Saturday morning until early Sunday morning that year in November, particularly heavy in the western parts of the County and County Durham, led to many lives being lost in the flood, as well as some miraculous stories of humanity, community spirit and courage.

Perhaps most catastrophic to many people was the collapse of the Tyne Bridge, a symbol of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne as notable in the 1770s as it is today. The middle arch and two of the arches near the south side of the bank collapsed at around 3am on the morning on the 17th November with the rapid swell of the water.

Mr Fiddas who lived at the north end of the bridge managed to escape his house with his wife and maidservant; but the maid begged him to go back with her to get a bundle she had forgotten. He agreed to return, so they turned back and moved along the bridge to get her possessions. Mrs Fiddas tragically watched as the arch gave way beneath her husband and servant. They were swept away by the river and never seen again. Six people died that night in Newcastle alone, and the flood was not limited to the one city. A description of the morning of the flood tells of the vast scope of the damage:

‘The first dawn of day discovered a scene of horror and devastation, too dreadful for words to express, or humanity to behold, without shuddering; all the cellars, warehouses, shops and lower apartments of the dwelling-houses, from the West end of the close to near Ouseburn, were totally under water.’

The walls of Black Church in Bywell were ruined, and the parish records destroyed. A copy of “The Account of the Great Flood in the Rivers Tyne, Tees, Wear and Eden” is available in the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle Upon Tyne’s collection which is located in the Library.

This vividly recounts how ‘dead bodies and coffins were torn out of churchyards and the living and the dead promiscuously clashed in the torrent.’ Mr Fenwick of Bywell kindly gave relief in the aid of money to those who had suffered and lost property. Indeed several touching stories emerged from the awfulness of the flood.

Many people did lose their lives, but many more were saved. Near Shields a cradle was found floating in the water with a baby inside, still alive. And people were not the only lucky escapees: a mercer, Mr Patton, discovered his house had been carried away nearly eight miles by the river. All of his possessions were gone, but his cat and a dog were still inside miraculously unharmed.

Peter Weatherly, a shoemaker and family survived because of the courage and help of a Gateshead bricklayer. Awakened at 3am from the noise of the flood, Peter Weatherly opened a window and saw Mr and Mrs Fiddas, two children and a maid passing along the bridge; he was perhaps the last person ever to see Mr Fiddas and his maid alive. Peter managed to get his children, wife and servant girl to safely leave the house, at great risk to all their lives after one of the arches of the bridge against the house collapsed. However, they were then stranded on the roof in the cold November morning for six hours by two arches that had fallen in around them. Several people had seen them stuck there but had not dared rescue them, until a bricklayer bravely made his way along adjoining shop roofs to get them all to safety at 10 o’clock the next morning.

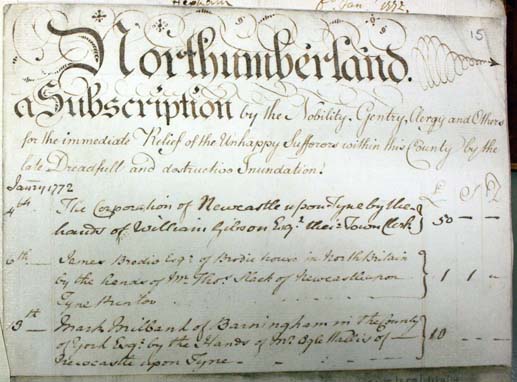

On December 19th 1771, gentlemen of Northumberland met at Hexham in a committee which agreed to pay those who had suffered and lost the most. The Great North Museum: Hancock library currently has the original River Tyne Flood Papers containing the handwritten outcome of the meeting, lists of wealthy subscribers who had agreed to send money, and of the claims sent in by the people of Northumberland, all which tell a fascinating story.

The Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle Upon Tyne are in the process of transcribing the flood papers, a wonderful and enlightening project. The contents page can be found on their website at http://www.newcastle-antiquaries.org.uk/Flood/contents.php

After the flood it took many years to recover the buildings, land, and the area to what it had been before; there was of course no replacement for those who had lost loved ones in the raging waters. But reading the accounts of this terrible night, there is a great feeling of humanity and a community spirit from these stories that enabled many who might have perished to have lived to tell the story.

The Great North Museum: Hancock Library is located on the second floor of the Museum. It has a wonderful collection of books on the history, heritage, archaeology and natural history of the northern region and it is free to use and open to everyone.

6 Responses to The Great Flood of November 1771 – guest post by Emily Needle