Written by Lizzie Jacklin, Keeper of Art, Hatton Gallery

The Hatton Gallery’s permanent collection of over 3300 artworks includes objects ranging from paintings and sculptures to watercolours and posters. Around 1300 of these objects are prints. Sadly our plans to show a large group of prints from the collection in an exhibition this summer are on hold due to the current situation, but some of you might be interested to read more about our print collection in the meantime.

A (very!) brief introduction to artists’ prints

Prints are works of art made by printing onto a surface (usually paper) from a specially prepared block or plate. Prints usually exist in multiples as more than one ‘impression’ (or copy) of the block can be taken. Although many copies of a particular print might exist, prints made specifically as new works in the print medium are still original works of art.

Artists have been making prints for centuries, both to bring their work to a wider audience and to engage creatively with printmaking. Some of the most famous artists in the history of western art – such as Rembrandt and Picasso – have been printmakers as well as painters.

There are lots of different printmaking techniques – too many to explain in this post! They range from relatively simple methods that it might be possible to try at home, such as potato printing and linocut, to more complex processes requiring specialist studio equipment, such as etching.

Prints in the Hatton Gallery collection

The prints in the collection were acquired over the course of a century or more. They are primarily western examples, with sheets dating from the Renaissance to the present day. Areas of particular interest include: a group of works by the Newcastle illustrator and wood engraver Thomas Bewick; a sizable grouping of nineteenth and early twentieth-century etchings by artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler; and British colour prints from the latter half of the twentieth century. The non-British artists represented include Piranesi and Goya.

It’s difficult to choose, but here are five of my favourites:

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), View of the Salario Bridge from Views of Rome,1754, etching on paper

This etching is from Piranesi’s print series The Views of Rome. The series includes depictions of some of the city’s best-known sites, from churches to ruins. It was so popular during Piranesi’s lifetime that he reissued it numerous times, a process continued by his sons after his death.

The subject of this print is the historic Salario Bridge. The distinctive tower topping the structure dated from the eighth century, while the main part of the bridge was even older. In his etching, Piranesi captured a sense of the grandeur and history of the bridge. Signs of decay – such as the plant-life overtaking the structure – are combined with a lively scene in terms of human activity. The bridge was later damaged during Napoleon’s invasion of Rome, and eventually demolished. As a result, this print is now also an important record of the historic structure.

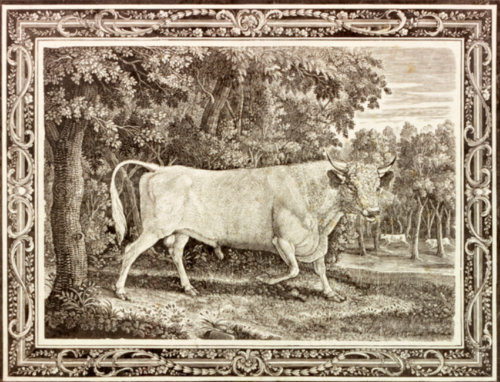

Thomas Bewick (1753–1828), The Chillingham Bull, 1789, wood engraving with letterpress on paper

Thomas Bewick is remembered as the first master of the ‘wood engraving’ technique, which he used to illustrate natural history books including his History of British Birds. The technique involves using a fine tool to engrave directly into wood: in Bewick’s hands it allowed for the creation of incredibly intricate and detailed scenes.

The Chillingham Bull, which was published here in Newcastle,is one of Bewick’s most celebrated prints. The text on the print explains that Bewick’s composition shows ‘the ancient Caledonian Breed’ of bull, which was – and still is – present in the park at Chillingham Castle in Northumberland.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), En plein soleil,1858, etching and drypoint on paper

En plein soleil, or In Full Sun, is from Whistler’s ‘French Set’, the first group of prints he published after taking up etching seriously. The subjects vary from genre scenes to studies of the artist’s friends. This print was probably made in Paris and likely depicts one of Whistler’s acquaintances. It is thought that Whistler drew the figure outdoors, working from life.

Etching has often been favoured by artists, as it allows them to ‘draw’ quite freely onto a prepared metal plate. The plate is then ‘bitten’ in acid: this process incises the artist’s marks into the metal plate so that they hold ink and a print can be made.

Antoni Tàpies (1923–2012), Visca Catalunya from Poems from the Catalan, 1973, lithograph on paper https://collectionssearchtwmuseums.org.uk/#details=ecatalogue.326916

In the early 1970s Tàpies made many works in response to the situation of his native Catalonia, which had been self-governed until the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, when Franco ended its autonomy. The images often contain elements of writing, which reflect both pride and a sense of protest. The words “Visca Catalunya!” seen on this print translate as “Long Live Catalonia!”, a common cry during the Franco period, when the Catalan language was actively suppressed. The print was published as part of Poems from the Catalan, a collaboration with the poet Joan Brossa.

Tàpies emphasised the importance of ‘always experimenting with new ideas and techniques’ in his work; he particularly enjoyed the technical experimentation that comes with printmaking.

Paula Rego (born 1935), The Baker’s Wife, 1989, etching with aquatint

https://collectionssearchtwmuseums.org.uk/#details=ecatalogue.548946

This piece loosely relates to the story of a heartbroken French baker who stops making bread when his wife has an affair with a shepherd. As is the case with many of Rego’s etchings, the story she had in mind at the outset is imaginatively reworked to the point of becoming both mysterious and unsettling. We see the sad baker in the background, while the foreground figures are presumably his wife and her lover.

Rego’s etchings are particularly admired for their mastery of light and shade, for which Rego employed a tonal etching technique called aquatint.

Reopening

We are not able to confirm an opening date yet, but we are hoping we may be able to open again in the autumn. We’re making sure we have everything in place so that when you visit it is as safe and enjoyable as possible and as soon as our opening date is confirmed we will share this with you. In the meantime, we hope you’re enjoying our digital content on our website and social media. Thank you for your continued support.

As a charity, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums rely on donations to provide the amazing service that we do and our closure, whilst necessary, has significantly impacted our income. Please, if you are able, help us through this difficult period by donating by text today. Text TWAM 3 to give £3, TWAM 5 to give £5 or TWAM 10 to give £10 to 70085. Texts cost your donation plus one standard message rate. Thank you.