A few weeks back I accepted a donation of a gold bracelet into TWAM’s collection. I am told that as a piece of jewellery it is unremarkable, but I think it is lovely. As TWAM’s maritime historian it is an unusual object to come to my attention, but an inscription on the inside of the bracelet’s clasp, “NEPTUNE SHELL SHOP Nov. 1918” provides a clue to its wider significance. The inscription connects the bracelet to the Neptune Engine Works of Tyne shipbuilders, Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, during the First World War, and thus into my subject area. Further research has shown that shell production by Neptune Engine Works was begun in response to the shell crisis of 1915, which seems to me like a good place to start.

In the spring of 1915 the shortage of high explosive shells, and its effect on the British offensive on the Western Front, created a political storm in Britain. (1) A failure to capture German fortified positions during the Battle of Aubers ridge was blamed on a lack of ammunition, with an article in The Times of 14th May 1915, demanding an increase in the supply of high explosive shells as quickly as possible. In contrast the French had been successful in their assault, and The Times correspondent had the figures to hand as to how they did it: “By dint of the expenditure of 276 rounds of high explosive per gun in one day, all the German defences, except the villages, were levelled with the ground,”. (2)

The response of the Government was swift, perhaps helped by the resignation of the First Sea Lord, Jacky Fisher, albeit over a different issue. The loss of Fisher forced the Prime Minister, Asquith, to dissolve his Liberal administration and replace it with a Liberal/Conservative Coalition. (3) On 25th May 1915, David Lloyd George, who had been Chancellor of the Exchequer, was appointed Minister of Munitions, a post created to address the shell crisis. Over the next year the energetic Lloyd George transformed munitions production to ensure that the guns at the front were well supplied with shells. One of the ways he did this was to approach engineering works that already possessed the requisite skills and experience, and encourage them to take on the business of shell manufacture. (4)

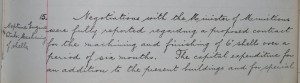

At the Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson board meeting of 21st October 1915, negotiations with the Minister of Munitions were reported regarding a proposed contract for the machining and finishing of 6” shells over a period of six months. The Capital expenditure for an addition to the present Neptune Engine Works buildings and for special machines was estimated at £25,000, and it was expected that the six months work would realise a profit of £36,000. The directors agreed to proceed with the scheme provided they could make satisfactory arrangements with the Minister of Munitions and with the Trade Unions and workmen already employed at the Neptune Works.

George Burton Hunter, Chairman of the Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson Board 1903 -1928. In 1918 he was knighted for his war services.

Over the next six months the project progressed rapidly. By the meeting of 16th December, the contract had been arranged, the new building was being prepared and a dozen or so of the machines had been installed. At the same meeting a proposal was put forward to enter into a further contract with the Minister of Munitions to make 2,000 six inch shell forgings per week. The Board of Directors favoured the proposal and authorised expenditure of £4,000 to £5,000 on a hydraulic press and other plant for this purpose.

At the meeting of 17th February 1916, it was reported that the hydraulic press had been erected and arrangements made to increase the manufacture of shell forgings to 4,000 per week. A second hydraulic press was to be purchased but “the total outlay authorised by the Board will not be exceeded.” The total outlay could have been up to £30,000, but the expected profit on 6 months of machining and finishing shells was £36,000, without taking into account the profit on the 104,000 shell forgings that would be made in six months. It seems to me that this was very good business indeed! (5)

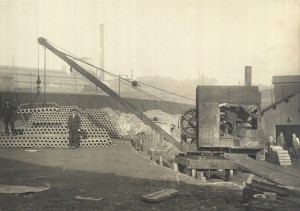

6″ Shell bodies being stacked outside the shell forge in Neptune Engine Works. TWAS : DS.SWH.5/3/2/3/2

There had been labour shortages in shipyards and marine engineering works right from the start of the war when men rushed to join the army and navy. Conscription for single men aged between 18 and 41 had been introduced on the 24th January 1916. Recruitment for the Neptune Shell Shop will have been taking place at around this time so it is unsurprising that photographs taken in October 1917 show a largely female workforce. We don’t have records of the ratio of men and women employed, but The Hartlepool National Shell Factory, a similar shell manufacturing operation set up in the Central Marine Engine Works, employed 365 women and 85 men, a ratio of 4 to 1. (6) General views of the Neptune Shell Shop show roughly 4 times as many women as men.

By the meeting of 18th April, shell forging had commenced, as had the machining of shells in the ‘Shell Shop’ – the exact words that appear in the inscription on the bracelet.

So, if we return to the bracelet for a moment, we are fortunate that we know the name of its owner and a little bit about her. Jane Ellen Bell was from South Shields and she worked in a Shell Shop during the First World War. Taking into account the inscription on the bracelet I think we can safely say that she worked in the Neptune Shell Shop. Her family and friends called her “Jenny”. We don’t know exactly when she started work in the Shell Shop, but when shell making began in 1916 she would have been about 31 years old. The “Nov.1918” date on the bracelet makes it likely that she worked there until the end of the war. Jenny Bell never married, but in 1933 she successfully prosecuted her fiancé for breach of promise. She had been engaged to Ferno Fountain for 17 years when he called off the marriage. Jenny was awarded £200 by the court.

These details were supplied by Mrs Brenda Croome, Jenny Bell’s great niece, who donated the bracelet to the museum. What we don’t know is how her great aunt came by this bracelet. It seems unlikely that every female employee received such a lovely gift from their employer to mark the end of the shell contract. If Jenny was a supervisor then perhaps it could have been a gift from the company in recognition of a job well done, but we just don’t know. Could it have been a gift from an admirer, perhaps the dastardly Ferno Fountain, or did Jenny want to mark the importance of her work in the Shell Shop by buying the bracelet for herself and having the inscription put on it?

Has anybody seen another bracelet like this, or something similar from a different shell works? Does anybody have a photograph of Jane Ellen, “Jenny”, Bell? Please add a comment if you can answer, or want to speculate on, any of these questions.

The bracelet is now on display in Coal, Ships and Zeppelins: North Tyneside in the First World War at Segedunum Roman Fort and Museum, Wallsend. The exhibition runs until 26th April 2015.

In Part 2 I will use contemporary photographs of work going on in the Neptune Shell Shop to illustrate how 6” shells were forged, machined and finished, ready for filling with high explosive.

1 – Wikipedia – Shell Shortage of 1915 – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_Crisis_of_1915

2 – The Times Digital Archive 1785 – 2006

3 – Massie, Robert K, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the winning of The Great War at Sea, P483 – 91, Vintage Books 2007.

4 – Wikipedia – David Lloyd George http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Lloyd_George

5 – Tyne & Wear Archives, Board of Directors Meeting Minutes DS.SWH/1/4/3

6 – Clarke, J F, Building Ships on the North East Coast: A Labour of Love, Risk and Pain, Part 2 c1914 – c1980, P207, Bewick Press 1997. See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3zA9QB5m1GE for a piece about the Hartlepool National Shell Factory created as part of Hartlepool’s Heroism and Heartbreak project to commemorate the First World War.